Thomas Onwhyn’s London

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF ‘ON CHRISTMAS DAY’ FOR £10

Born in Clerkenwell in 1813 as the eldest son of a bookseller, Thomas Onwhyn created a series of cheap mass-produced satirical prints illustrating the comedy of everyday life for publishers Rock Brothers & Payne in the eighteen forties and fifties.

In his time, Onwhyn was overshadowed by the talent of George Cruickshank and won notoriety for supplying pictures to pirated editions of Pickwick Papers and Nicholas Nickleby, which drew the ire of Charles Dickens who wrote of “the singular Vileness of the Illustrations.”

Nevertheless, these fascinating ‘Pictures of London’ that I came upon in the Bishopsgate Institute demonstrate a critical intelligence, a sly humour and an unexpected political sensibility which speaks powerfully to our own times.

In this social panorama, originally published as one concertina-fold strip, Onwhyn contrasts the culture and lives of rich and the poor in London with subtle comedy, tracing their interdependence yet making it quite clear where his sympathy lay.

The Court – Dress Wearers.

Dressmakers.

The Opera Box.

The Gallery.

The West End Dinner Party.

A Charity Dinner.

Mayfair.

Rag Fair.

Music of the Drawing Room.

Street Music.

The Physician.

The Medical Student.

The Parks – Day.

The Parks – Night.

The Club – The Wine Bibber.

The Gin Shop – The Dram Drinker.

The Shopkeeper.

The Shirtmaker.

The Bouquet Maker.

The Basket Woman. (Initialled – T.O. Thomas Onwhyn)

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to take a look at

Malcolm Tremain’s Spitalfields

Jonathan Pryce will read my short story ‘On Christmas Day’ at the launch at Burley Fisher Books in Haggerston tonight Thursday 23rd November at 6:30pm.

CLICK HERE FOR TICKETS

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY FOR £10

In 1981, when Malcolm Tremain was working as a Telephone Engineer in Moorgate, he bought an Olympus 0M1 and set out to explore his fascination with Spitalfields.

‘I used to come over and wander round whenever I felt like it,’ he admitted to me, ‘I never thought I was making a record, I just wanted to take interesting photographs.’ Malcolm’s pictures of Spitalfields in the early eighties capture a curious moment of stasis and neglect before the neighbourhood changed forever.

Passage from Allen Gardens to Brick Lane – ‘I asked this boy if I could take his picture and he said, ‘yes.’ When I looked at the photograph afterwards, I realised he had one buckle missing from his shoe.’

Spital Sq, entrance to former Central Foundation School now Galvin Restaurant

In Spital Sq

In Brune St

In Toynbee St

Corner of Grey Eagle St & Quaker St

In Quaker St

Off Quaker St

Outside Brick Lane Mosque – ‘People dumped stuff everywhere in those days’

In Puma Court

Corner of Wilkes St & Princelet St

In Wilkes St

Outside the Jewish Soup Kitchen in Brune St

Outside the night shelter in Crispin St – ‘He was shuffling his feet, completely out of it’

In Crispin St

In Bell Lane

In Parliament Court

In Artillery Passage

In Artillery Passage

In Middlesex St – ‘note the squint letter ‘N’ in ‘salvation”

In Bishopsgate

In Bishopsgate

Petticoat Lane Market

In Wentworth St

In Wentworth St

In Wentworth St

In Wentworth St

In Wentworth St

In Fort St

In Allen Gardens

In Pedley St

In Pedley St

In Pedley St – ‘Good horse manure available – Help yourself – No charge’

At Pedley St Bridge

In Sun St Passage at the back of Liverpool St – ‘Note spelling ‘NATOINE FORANT”

In Sun St Passage

Photographs copyright © Malcolm Tremain

You may also like to take a look at

David Hoffman at Fieldgate Mansions

Philip Marriage’s Spitalfields

Morris Goldstein, The Lost Whitechapel Boy

Jonathan Pryce will read my short story ‘On Christmas Day’ at the launch at Burley Fisher Books in Haggerston this Thursday 23rd November at 6:30pm.

CLICK HERE FOR TICKETS

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY FOR £10

Morris Goldstein, self-portrait

There is a lecture to celebrate the publication of a new book about Goldstein’s life and the rediscovery of a significant artist of the East End. The talk will be introduced by Professor Rebecca Beasley, an expert in Modernist Studies at Oxford University, and presented by Morris Goldstein’s son Raymond Francis who has been researching his story for the last ten years.

Click here to book for the lecture at the Hanbury Hall on Tuesday December 5th

When Raymond Francis showed me these pictures by his father Morris Goldstein – seeking to bring them to a wider audience and reinstate his father’s position among the Whitechapel Boys – I was touched by the tender human observation apparent in Morris’ sympathetic portraits of his fellow East Enders.

The Whitechapel Boys were a group of young Jewish artists from the East End, including the poet Isaac Rosenberg, who showed together at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1914 and made a distinctive contribution to British Modernism in the early twentieth century. Yet when the list of those who comprise this group is made – including Mark Gertler, David Bomberg and others – the name of Morris Goldstein is rarely mentioned.

It was the death of Morris Goldstein’s father that forced him to leave the Slade early, in order to earn money to support his family rather than pursue his art, with the outcome that – although he exhibited a significant number of works in the 1914 Whitechapel show – his work has subsequently become unjustly neglected.

More than century later, it is is time for a re-evaluation of the group that became known as the Whitechapel Boys and a re-examination the life and work of those artists who became marginalised. And, thanks to Raymond Francis, we are to learn Morris Goldstein’s story at long last.

Born in Poland in 1892 in Pinczow, a small town midway between Krakow and Warsaw, Morris Kugal emigrated to London at the age of six in 1898 with his parents David and Sarah, and his two younger sisters Annie and Jeannie.

Adopting the name Goldstein, the family lived in Redman’s Row, Stepney, where the poet Isaac Rosenberg was a neighbour. Growing up in poverty, Morris quickly came to understand the conflict between his dreams and reality. Although his talent led him to Stepney Green Art School, he knew that the need to leave and earn a living at fourteen years old would prevent him pursuing a career as an artist.

Like Rosenberg, he was obliged to take up an apprenticeship in marquetry but for three years they went together to evening classes in art close to their employment in Bolt Court, Fleet St, where Morris received the gold medal for best work and found himself alongside fellow students including Paul Nash. Determined to become a respected painter, Morris soon fund himself in the company of other aspiring young artists, including Mark Gertler whom he first met at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1908.

Through tenacity and determination, Morris managed to overcome the obstacle of his financial disadvantage by winning a scholarship to the Slade School of Art which he attended alongside other Whitechapel Boys – Isaac Rosenberg, David Bomberg and Mark Gertler in 1912. He applied to the Jewish Education Aid Society in 1908, 1909 and 1911, before being granted twelve shillings and sixpence a week. While at the Slade, Morris and Isaac Rosenberg walked from Mile End to Gower St every day to save money and they often went to study at the Whitechapel Library, doing their homework which entailed sketching and studying the history of art, thus escaping the distractions of home life in the evening.

As this group of young East End artists acquired confidence, they discovered the Cafe Royal in Regent St where they encountered luminaries of the day, including members of the Bloomsbury Group and socialites such as Nancy Cunard and Lady Diana Manners. Morris hailed it as Mecca and recalled making his sixpenny coffee and cake last all day.

Often Morris and Isaac Rosenberg were joined on their walks by David Bomberg and they met Sonia Cohen, a Whitechapel girl brought up in an orphanage, whom they all fell in love with. Meanwhile, Isaac Rosenberg grew increasingly conscious of the burden imposed on his family by his long preparation for a career as a painter. Morris’ mother Sarah Goldstein was a close friend of Hacha Rosenberg, Isaac’s mother, and they commiserated that they knew of young tailors in the neighbourhood earning fifteen or twenty pounds a week, while their sons brought in nothing. In 1913, Morris’ father’s unexpected death placed the responsibility of becoming the breadwinner upon him and he had to give up his study to replace the income of two pounds a week that David Goldstein had earned as a shoemaker.

He had five works in the Whitechapel Art Gallery’s Twentieth Century Art Review of Modern Movements in May 1914, along with the other Whitechapel Boys (Rosenberg, Bomberg etc), the only time that this group ever exhibited together. When the First World War broke out in August of that year, Morris sought to enlist but was rejected because he was not yet a naturalised British citizen. David Bomberg was also rejected but Isaac Rosenberg was sent to the Somme where he was killed in April 1918.

During the war, Morris was Art Master at the Toynbee Art Club at Toynbee Hall and the Annual report of 1914 -1915 notes, “classes were well attended, the members being greatly assisted by the guidance and criticism of Mr Morris Goldstein, the art master.”

When the Jewish Education Aid Society wrote to Morris asking for their money back in 1917, he replied on Boxing Day in the following defiant terms –“I am alive and that is a great deal in these days. To be alive is a great benediction – to live through these turbulent times until peace reigns once more upon earth would be the greatest joy of all. My present hope and wish is to live through these times so that after the cessation of hostilities I could put my body and soul into my spiritual work. I am not yet in the army but of course I’m liable to be called up any day now. Let us hope the war will end soon, Believe me to remain, Morris Goldstein”

Morris continued to exhibit at the Whitechapel Gallery’s annual East End Academy until 1960.

Sarah & David Goldstein stand outside the East End boot shop that was the family business, c. 1912

Sarah and David Goldstein with their daughters Annie and Jeannie, and Morris on the right.

Morris Goldstein aged twenty when he went to the Slade in 1912

Morris Goldstein paints the portrait of the Mayor of Stoke Newington in 1960

Sketch of Morris Goldstein’s son, Raymond Francis, sleeping in 1955

Raymond Francis standing at the gates of Stepney Green School where his father was educated

Raymond Francis outside 13 Vallance Rd where his father lived and wrote the letter below.

In 1940, Morris Goldstein wrote to relatives in America seeking help to send his two daughters across the Atlantic to escape the war.

A local landmark, this unusual and attractive nineteenth century terrace 3-11 Vallance Rd in Whitechapel is currently under threat of demolition.

Artwork copyright © Estate of Morris Goldstein

Photograph of Vallance Rd terrace © Alex Pink

Rodney Holt, Designer & Set Builder

Jonathan Pryce will read my short story ‘On Christmas Day’ at the launch at Burley Fisher Books in Haggerston this Thursday 23rd November at 6:30pm.

CLICK HERE FOR TICKETS

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY FOR £10

It was my great delight to meet Rodney Holt of Mojo Productions, the creative mastermind responsible for London’s most famous window displays, at Fortnum & Mason for the past thirty years. This bright-eyed genius with a shock of white hair flits around his workshop in Brentwood, Essex, grinning excitedly as he oversees his extravagant creations and encourages his minions just like Father Christmas in that other fabled workshop at the North Pole.

Rod and his team of specialists were putting the finishing touches to the Christmas window displays before they were transported to Piccadilly. The walls were lined with huge wooden frames, the same size as the shop windows, and each one was filled with a sequence of exotic animated confections, rotating lobsters, flying puddings, champagne fountains, exploding crackers and a train set circling eternally. All around lay fragments of former displays, including golden carriages, giant nutcracker dolls and the man in the moon.

Wandering around this bizarre interior was like exploring the unconscious imagination of Santa himself – the workshop where dreams and fantasies are manufactured. Yet Rod’s crew of painters and model makers worked placidly at their tasks despite the phantasmagoric contents of their workplace. Readers will be relieved to learn that everything is under control for Christmas.

Rod & I retreated to his office, where a row of miniature shop windows contained the working models for this year’s displays. Here Rod told me his story and I was fascinated to learn how this overflowing of flamboyant creativity has its origins in the craft traditions of old East End.

“I was born in Bethnal Green but my family moved out to Essex after the war, when I was still a baby. There were jobs in Essex and my dad went to work at Ford’s in Dagenham and was there for forty years. Mum had ten children, so she was quite busy too. Her full name was Amy Rosina Goldring, so we think she might be Jewish. She came from an interesting family – one of her brothers was in the film industry in the early days, one did back-to-front sign writing with gold leaf, another had an accordion band in West End, The Accordionnaires, and her mother was a court dressmaker.

Dad was one of ten brothers and most of them worked in Spitalfields Market, some were traders but others used to make carts and barrows in the Hackney Rd. My dad was a French Polisher who kept a horse in Gibraltar Walk and used to make furniture deliveries on a flatbed cart. I remember him telling me that he used to deliver as far as Hampstead.

I left school and went to Hartley Green College, doing a course in Display & Exhibition Design. My career officer told me I should be a council tiler, that was the nearest they could get to an artistic career. So I said, ‘That’s no good,’ and I think it was my art teacher at school who suggested I do this. To be honest, I wanted to be a sculptor or a potter, but there were not many options then. If you wanted to be a potter, you worked on an assembly line in a pottery. I was at college for a couple of years and I did not learn a lot but I sorted out what I wanted to do. They did a day release scheme and I got sent to Selfridges in Oxford St. I got on well with everybody there and they said, ‘You’ve got a job here after you’ve taken your diploma.’ But I went to Paris instead of taking my diploma. I stole a mate’s bike out of an alleyway while he was away at university in Manchester and cycled off to France. When I came back, I went straight to Selfridges.

At Selfridges, I told them I knew nothing about fashion, so I could not be fashion dresser. I said, ‘I’d like to do all the toy windows and all the gardening windows,’ because those were the things I thought I could be more creative with. I was nineteen years old and they let me loose. I did one display where I had all the teddy bears marching out of the window which everybody liked. My idea was they were fed up and walking out. I got on alright there but I thought I do not really like this much. I wanted to join the team in the big studio up in the roof. I used to get on very well with all the guys there. After eighteen months, a couple of Australians who worked there and had come over land said, ‘We’re all fed up now, we think we should go off somewhere on a trip.’ I said, ‘That sounds good to me,’ and we went off to India. Mr Millard, the Managing Director, asked me, ‘Are you sure? Because the others have gone, you could move up the ladder.’ But I said, ‘No, I don’t want to go up the ladder, I’d rather go to India.’ He wished me all the luck in the world.

I only had a hundred quid but I made it to Kashmir by hitch-hiking, where my sister sent me another thirty quid to get home. It cost me six quid to get from Istanbul to London and I sold my blood to do it. When I got back, it all fell into place. Selfridges welcomed me back to work on the Christmas windows. I was lucky because it was the first time they were trying a different type of window. They did a set of windows that had no stock in them but told a story instead. The designer Peter Howitt had just finished the film of Alice in Wonderland and he was able to buy the sets. They gave us an old factory in Kensington where we sorted the scheme out. Pete asked for me, he said, ‘I’d like Rod because he doesn’t want to do window dressing really.’

Working freelance, I did all sorts – shops in the Kings Rd and themed pubs, clubs and bars. I worked for Peter on the original London Dungeon too. They gave me a mini with ‘London Dungeon’ on the side and an iron coffin on the roof! I had to be careful how I drove that about. I had quite a few contacts at Pinewood and Shepperton so I was able to purchase some great old props. We used to work overnight in the Dungeon and the stuff that happened was unbelievable.”

Rodney Holt, Designer, Set Builder & Model Maker

You may also like to read about

Edward Bawden On Liverpool St Station

Jonathan Pryce will read my short story ‘On Christmas Day’ at the launch at Burley Fisher Books in Haggerston this Thursday 23rd November at 6:30pm.

CLICK HERE FOR TICKETS

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY FOR £10

Liverpool St Station by Edward Bawden

Please come to our free SAVE LIVERPOOL ST STATION campaign event at 6pm tomorrow, Tuesday 21st November, at Bishopsgate Institute, 230 Bishopsgate, EC2M 4QH. No need to book, just come along. Speakers include Griff Rhys Jones, Eric Reynolds and Robert Thorne.

Edward Bawden made this huge linocut of a smoke-blackened Liverpool St in 1960. It extends to almost five feet in length, so long that to allow you to see the details of this epic work I must show it here in two panels. In order to print it, Bawden laid a board on top of the linocut and asked his students at the Royal College of Art to assist him by standing on top

When I first visited the station it was just like this and I remember it as a diabolic dark cathedral. As a one new to London, I arrived back from Cromer one Sunday on a late train after the tubes had closed and spent a terrifying night here, shivering on a bench. Sitting awake, I watched all through the small hours as the trucks rattled in and out of the station, racing down the slope onto the platforms, delivering newspapers and mail sacks to the waiting trains.

But as this print reveals, Edward Bawden had a keen eye for elegant nineteenth century ironwork and, even before it was cleaned up, he was alive to beauty of the station. Contemplating Liverpool St on the BBC television programme Monitor in 1963, he said “I think the ceiling is absolutely magnificent, it is one of the wonders of London.” And he knew it well, because for nearly sixty years – between 1930 and 1989 – he travelled regularly through the station, whenever he took the train back and forth between London and Braintree station, just one mile from his home at Brick House in Great Bardfield, Essex.

He is one of my favourite twentieth century British artists and the span of Edward Bawden’s career is almost as wide as the Liverpool St arches. After leaving the Royal College of Art, he began designing posters for London Transport in the nineteen twenties, then became a war artist in World War II and was busy creating prints and paintings, alongside murals, wallpapers, commercial illustration and design, right up until the late eighties. I particularly admire his unique bold sense of line that gave an unmistakably appealing graphic quality to everything he touched.

John Thomas Smith’s Rural Cottages

Jonathan Pryce will read my short story ‘On Christmas Day’ at the launch at Burley Fisher Books in Haggerston next Thursday 23rd November at 6:30pm.

CLICK HERE FOR TICKETS

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY FOR £10

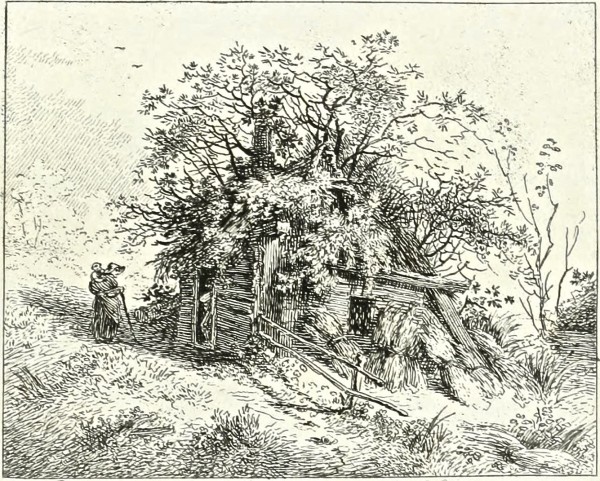

Near Battlebridge, Middlesex

Once November closes in, I get the urge to go to ground, hiding myself away in some remote cabin and not straying from the fireside until spring shows. With this in mind, John Thomas Smith’s twenty etchings of extravagantly rustic cottages published as Remarks On Rural Scenery Of Various Features & Specific Beauties In Cottage Scenery in 1797 suit my autumnal fantasy ideally.

Born in the back of a Hackney carriage in 1766, Smith grew into an artist consumed by London, as his inspiration, his subject matter and his life. At first, he drew the old streets and buildings that were due for demolition at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Ancient Topography of London and Antiquities of London, savouring every detail of their shambolic architecture with loving attention. Later, he turned his attention to London streetlife, the hawkers and the outcast poor, portrayed in Vagabondiana and Remarkable Beggars, creating lively and sympathetic portraits of those who scraped a living out of nothing but resourcefulness. By contrast, these rural cottages were a rare excursion into the bucolic world for Smith, although you only have to look at the locations to see that he did not travel too far from the capital to find them.

“Of all the pictoresque subjects, the English cottage seems to have obtained the least share of particular notice,” wrote Smith in his introduction to these plates, which included John Constable and William Blake among the subscribers, “Palaces, castles, churches, monastic ruins and ecclesiastical structures have been elaborately and very interestingly described with all their characteristic distinctions while the objects comprehended by the term ‘cottage scenery’ have by no means been honoured with equal attention.”

While emphasising that beauty was equally to be found in humble as well as in stately homes, Smith also understood the irony that a well-kept dwelling offered less picturesque subject matter than a derelict hovel. “I am, however, by no means cottage-mad,” he admitted, acknowledging the poverty of the living conditions, “But the unrepaired accidents of wind and rain offer far greater allurements to the painter’s eye, than more neat, regular or formal arrangements could possibly have done.”

Some of these pastoral dwellings were in places now absorbed into Central London and others in outlying villages that lie beneath suburbs today. Yet the paradox is that these etchings are the origin of the romantic image of the English country cottage which has occupied such a cherished position in the collective imagination ever since, and thus many of the suburban homes that have now obliterated these rural locations were designed to evoke this potent rural fantasy.

On Scotland Green, Ponder’s End

Near Deptford, Kent

At Clandon, Surrey – formerly the residence of Mr John Woolderidge, the Clandon Poet

In Bury St, Edmonton

Near Jack Straw’s Castle, Hampstead Heath

In Green St, Enfield Highway

Near Palmer’s Green, Edmonton

Near Ranelagh, Chelsea

In Green St, Enfield Highway

At Ponder’s End, Near Enfield

On Merrow Common, Surrey

At Cobham, Surrey – in the hop gardens

Near Bull’s Cross, Enfield

In Bury St, Edmonton

On Millbank, Westminster

Near Edmonton Church

Near Chelsea Bridge

In Green St, Enfield Highway

Lady Plomer’s Place on the summit of Hawke’s Bill Wood, Epping Forest

You may also like to take a look at these other works by John Thomas Smith

John Thomas Smith’s Ancient Topography of London

John Thomas Smith’s Antiquities of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

Harry Harris, Lighterman

Jonathan Pryce will read my short story ‘On Christmas Day’ at the launch at Burley Fisher Books in Haggerston on Thursday 23rd November at 6:30pm.

CLICK HERE FOR TICKETS

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY FOR £10

Workers on the Silent Highway

These excerpts are from the account by Harry Harris entitled Under Oars, Reminiscences of a Thames Lighterman 1894-1909, written in a ledger which was passed on to his son Bob Harris and published by Stepney Books in 1978.

“At the age of thirteen, I was asked, ‘What do you want to be?’ The answer was obvious. Aunt Louie wondered whether Harry boy would like to become a missionary? I said, ‘A lighterman or perhaps go to sea?’ I was then warned of the dangers of these two jobs. The true story was related about a ship-wrecked crew eating the boy. Rather cheekily, she was reminded that missionaries had met the same fate.

Father was then a foreman for W. Pells & Son and had an opportunity of having me with him to get some experience, or perhaps a warning, before the actual apprenticeship. In June, 1894, I saw the opening of Tower Bridge by the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, who was aboard the leading vessel. A large number of guests were invited to view the scene from one of Pells’ barges moored below London Bridge, and refreshments were provided. I was the boat boy and busy with the passengers to and fro. Pocket money was scarce in those days for me, but I was not allowed to accept any money or tips. I can still feel the itch in my hand to pick up sixpences and coppers.

On the 14th August, 1894, I was apprenticed to my father. A brother foreman wanted a handy boy, so arrangements were made for me to commence at twelve shillings a week, but after two weeks work – the governor having seen me – he decided that my size of boy was only worth ten shillings. My father was indignant, so he took me into his firm at twelve shillings a week.

The following winter was the coldest for years, the river becoming unnavigable owing to the ice. Heavy snow having fallen in the London district, the City Council dumped the snow into the river. Every bridge and embankment saw this dumping going on day after day, it quickly froze together forming ice floes. The ice adhered to barges, and many broke adrift and were to be seen floating up or down river. But looking back on that time, the remaining impression is they were light-hearted days. We found fun all the time, hours were long, work was strenuous, yet I cannot remember any dissatisfaction with my sphere in life. Summertime always compensated for Winter.

I must wander from this journey to mention the fog. The river then becomes a black area, if one was suddenly caught. One would never start in a dense fog but, if caught in one, might carry on and be lucky to finish the job. The ears became eyes, and all senses alert to get a bearing, yelling out to anchored craft, ‘Where are you?’ Fog is the worst enemy of river work. Signs of fog can be observed but indications of its clearing other than a breeze are very few.

We young lightermen were rather clannish and somewhat despised the ‘landsman.‘ Our chief topic of conversation was the river or life on the river. This had a language of its own, so I presume that our shore friends were often fed up by attempting to listen to an account of an incident in the day’s work given in the vernacular. You either ‘fetched’ or ‘went by,’ ‘saved tide’ or ‘lost tide.’ Arches were called ‘bridge holes.’ Flood tide work was ‘bound up along,’ ebb the reverse. The point was the ‘pint.’ The Quay man would be bound to ‘K dock,’ or ‘the German,’ or ‘the Batty,’ ‘down the Vic and dock her’ or perhaps ‘Jack’s Hole.’ The creek was always ‘crick.’ Back-slang was often used, cabin becoming ‘nibac’ and so on.

A large number of lightermen went by nicknames, all very apt, either featuring physical or psychological defects or assets, such as Tubby, Podge, Narrow, Rasher, Dabtoe, Winkle-eye, Hoppy, Humpy and Wiggy. Little Biggie was a tiny man of that name. Man Green was the smallest ever. Titty Mummy was about six foot two and big in proportion. Happy Wright, Bosco Dean, Whisper Rivers, Moaner, Doctor Brooks, Mad Brady, Bonsor Corps, Knocker, Knacker, Knicker, Sancho, Pongo, Walloper, Curly, Gingers, Coppers and Snowies. Robinsons were Cockies, Blythes were Nellies, Hopkins and Perkins, Pollys. Mashers, Starchers, Stiffies and Rum and Rags. Fireworks, Redhot, Burn’em, Never Sweat, Dozey, Slowman, Squibs, Gentle Annie, Soft Roe, and Pretty.

‘A full roadun’ was a week’s work including Sunday and nights. A ‘thgin’ (tidgeon) was an easy night. Tarpaulins were ‘cloths,’ extra rope a ‘warp,’ oars ‘paddles’ and a pump was the ‘organ.‘ Tugs were ‘toshers,’ the space aft of the cabin bench was ‘Yarmouth Roads.‘ Anchor the ‘killick.’ If a lighterman had a ‘waxer’ (cheap drink) for a friend, he would be told that ‘there was one behind the pump.’ The dock official whose duties were to enforce charges on craft when incurred was and still is the ‘Bogie Man.’ The ‘ditch’ is the river, ‘fell in the ditch’ is falling overboard. ‘Gutsers,’ ‘sidewinders,’ ‘chimers,’ ‘stern butt’ (always a more vulgar word is used) and ‘glancing blow’ were terms describing blows to craft by collision with other craft.

When reporting damage, a man would often say ‘ just a glancing blow,’ especially if he was responsible. These were viewed suspiciously by the foreman. I worked under a foreman to whom this term was a ‘red rag.’ Lightermen were ever optimistic!”

Harry Harris, Lighterman, photographed in 1947.

Photographs courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may also like to read